Gothic and the golden ratio

speculative geometry, like the other sciences, has its games and its uselessness.

Châteaubriant

On the previous page, I invalidated the relevance of mathematics alone in the analysis of Gothic tracery. Logically, this excludes the use of the golden ratio. Indeed, while the golden ratio can be expressed geometrically, the fact remains that its interpretation, the very idea of its singularity as an irrational number, places it squarely in the lap of mathematics.

Isn't it universally accepted that the golden ratio governs the layout of cathedrals?

Let's start with a reminder for those unfamiliar with this relationship. It is represented by the Greek letter Phi, symbol φ. Its numerical value, 1.618, offers some curious mathematical properties:

φ - 1 = 0.618

1/ φ = 0,618

φ = 1,618

φ + 1 = 2,618

φ / 0,618 = 2,618

φ x φ = 2.618

0,2618*12 = 3,1416

This ratio can be obtained using very simple geometric plots. For example, as shown in Fig. 1, all you have to do is determine half the base of a square, i.e. point M, in order to draw a circular arc of radius MD that intersects the extension of the line at C.

The ratio between segments AB and AC gives φ, the golden ratio. The rectangle we've just formed expresses a golden rectangle, as does the figure as a whole. We'll return to this same layout in a few lines.

Fig. 1 - Geometric construction of the golden ratio

The golden ratio is used for many purposes. It's supposed to provide the most beautiful aesthetic proportion, regulate the growth of our genes or direct the dimensions of the Khufu pyramid. Nothing less.

But what's the historical background? It is often claimed that Pythagoras held the secret. This is to forget that the golden ratio is an irrational number. Limited to integers, Pythagoras abhorred them. They challenged his geometric interpretation of the world, in which every number is a length. Even if they existed, nobody was supposed to know about them. Legend has it that his disciple, Hippasius of Metapontum, was drowned simply for talking about it. In any case, between knowing about the existence of a thing and understanding it mathematically, there was a step that Greek knowledge could not take.

So why invoke Pythagoras against all historical plausibility? The reason probably lies in the Pythagorean school's choice of the pentagon as a sign of recognition. The reasoning is simple: the geometry of the pentagon expresses the golden ratio; therefore, Pythagoras knew the golden ratio! This is a perfect example of paralogism, or even sophistry in the arguments of some...

Euclid later noted this relationship "in extreme and average reason", without realizing its significance. He would have had to be able to calculate its algebraic value, something that the time was incapable of doing. A translation of Euclid by the geometrician monk Campanus from Novara was indeed made in the 13th century, but his commentaries were not published until 1409. The Gothic period was over.

Much later, in the early 16th century, the monk Lucas Pacioli di Borgo studied it in his De divina proportione. For him, geometric proportion proved the existence of God. This was the genesis of the famous "Divine Proportion".

In the 19th century, it was the turn of the German philosopher Adolf Zeising to take an interest in this relationship. He called it the "golden section". For him, it was an aesthetic system that he sought to discern in all fields, including biology and architecture.

But the modern infatuation with this number owes everything to Prince Matila Costiesco Ghyka, author of the indispensable Le nombre d'or. For those who refer to it, it forms an aesthetic proportion, a mathematical message presiding over all ancient artistic and architectural conceptions.

But the only thing I'm interested in here is whether medieval builders used the golden ratio, because it's an established fact, as we're regularly told.

To verify this, I have studied dozens of monuments, following the example of M. Labouret(whose work I highly recommend). For example, the transept of Strasbourg cathedral is supposed to have the same ratio of external length to internal width. Here's where the problem lies: "Too bad if one of the two figures includes the thickness of the walls and buttresses and the other doesn't"

And on this point, I can only agree with him. You can't establish a relationship between a benchmark located inside a structure and one located outside. This is a gross methodological error, to which I shall return later.

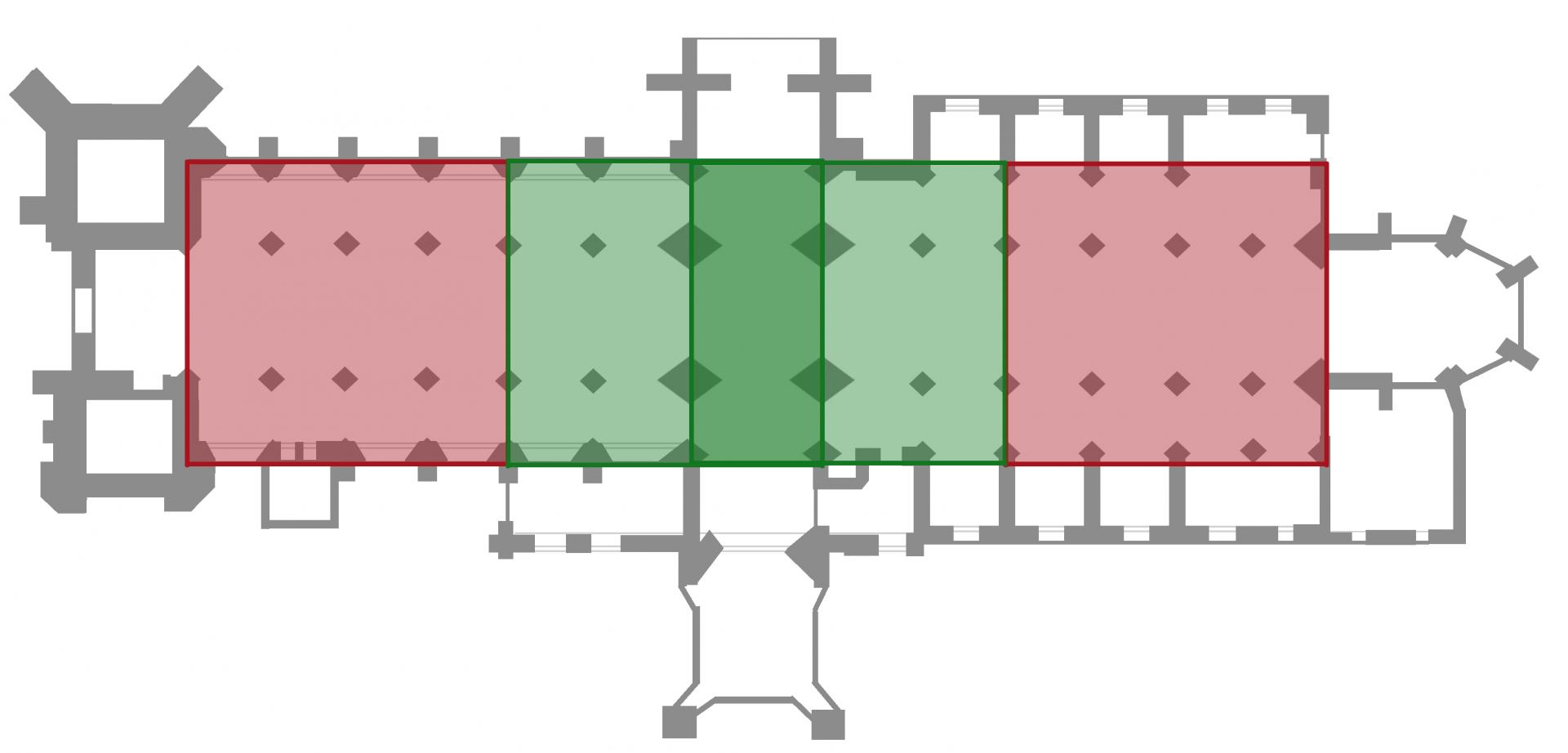

Let's turn now to Dol-de-Bretagne Cathedral. It is often presented as having a floor plan governed by golden rectangles. Several studies have been devoted to it. In this study, a geometric construction has been superimposed on the plan of the building. It consists of four squares, two of which overlap at the level of the transept, which is central here (fig. 2).

Fig. 2 - The four supposed squares

Now, if we cut the overlapping squares along the lines of the transept, we can obtain three rectangles containing a golden ratio (two are formed by the union of the pink and light-green polygons, the last by the two central squares). The whole is equivalent to two symmetrical tracings of a golden rectangle (like the one in fig. 1), each in a double square (fig. 3). Now, if we merge the unused spaces of the long squares, we obtain the surface of the transept and the plan of the building.

It's all very elegant, and you'd be forgiven for thinking that the golden ratio governs the spaces of this cathedral. There are, however, a number of awkward points in this theory.

First and foremost, the layout. Here, I've roughly redrawn it for greater legibility, but the original(see the study) seems to be of dubious quality. This is a recurring problem, which I'll discuss in a few pages.

Cause or consequence, the squares posed as premises are not. They are distorted and not exactly the same size. We'd need a good-quality survey to go any further.

The second point is the absence of a frame of reference, a working methodology. While the vertical lines of the polygons follow the centers of the pillars, the horizontal lines are aligned with the outer wall on the left and with the outside of the pillars on the right. This is illogical and unacceptable. The proposed layout is therefore different from what it should be. As a result, the squares that weren't squares in the first place aren't squares at all, and the golden proportions are lost.

Fig. 3 - The two symmetrical golden lines

The same applies to my attempt to retrace figure 3, which, based on the proportions of the study, is totally misleading. To the layman, the demonstration may seem credible, but architecturally and mathematically speaking, it's simply wrong.

Matila Ghyka would not have been moved by these inconsistencies. He invoked the "trembling", the "groping of the living", to justify the discrepancy between his constructions and the plans.

The same applies to the most emblematic of Gothic cathedrals, Notre-Dame de Paris. Here, the golden ratio is supposed to appear in the proportions of the façade. If you divide the length of the façade (approx. 69 m) by its width (approx. 40 m), you get the Golden Ratio (approx. 1.618) (normally, with the given dimensions, you'd get 1.725, but you'll notice that this result is quite close to the Golden Ratio). Note that the height must take into account the embellishments on the roofs of the towers). We can conclude that the façade was built according to the rules of the Golden Number

Note the obligation to take into account the "embellishments" and the numerous "surroundings", which make any calculation impossible. It is therefore impossible to judge the announced delta between the hoped-for result and the actual result.

According to the TV program "C'est pas sorcier", the proportions of the Paris floor plan are also governed by golden rectangles. In fact, it's claimed that all cathedrals are built to this proportion.

To demonstrate this assertion, journeyman carpenter Renaud Beyfette was called in. Compass in hand, he can be seen virtuously tracing the area of the cathedral. It's a golden rectangle. It's a striking image, and that's exactly the point.

The video starts directly on this passage >>>

Let's overlook the fact that the construction used exceeds the cathedral's footprint and that, in the end, there is no correspondence with an architect's plan. The inconvenient point is that it was impossible for me to obtain anything other than an approximate result with this method. And let's not forget that even an exact explanation would solve nothing, explain nothing. What about the interior proportions, the construction of the transept, the rhythms of the bays or the design of the chevet? It is curious that a talented journeyman carpenter, a specialist in medieval war machines, should propose a speculative layout instead of seeking an operative solution in keeping with medieval tradition.

The same is true of the Cistercian abbey of Le Thoronet, and I quote Mr. Labouret here: "if we stretch the dimensions a little, we interpret the basic module as almost a golden rectangle. And we put on the real plans a certain number of geometric figures that don't even correspond to the structural points of the monument, in order to deduce dimensions corresponding to what we want to demonstrate..."

This is the crux of the matter. the frontispiece to Plato's Academy reads: "No one enters here who is not a geometer". Geometry and architecture are sciences, and as such require a minimum of knowledge and rigor, qualities that many people clearly believe they possess, wrongly.

George Jouven, chief architect of historic monuments and an undisputed specialist in arithmology, talks about the golden ratio in the 13th century. Whatever Villard de Honnecourt's drawings may lead us to believe," he says, "the Middle Ages had forgotten it. Viollet-le-Duc himself, in his chapter on proportions, says nothing about it. Clearly, the man behind the cathedrals never came across this relationship, nor did Vitruvius or any other architect.

Let me make it clear that I'm not waging war on the golden ratio - quite the contrary. My only question is whether it was known in the Gothic period. According to my research, the answer is clearly negative. However, some researchers may have been misled. There are constructions that are graphically very close to φ. A ratio of 5/8 gives 0.625, while that of 3/5 gives 0.6. These differences are almost negligible from an operative point of view.

Furthermore, we'll see later that some plans are organized on a double square, the long square, whose diagonal is the square root of five. Now, this irrational number (2.236) is nothing less than the addition of 1.618 + 0.618, i.e. φ + 1/φ. Clearly, the use of simple squares is not a deliberate expression of the golden ratio.

If we look for it compulsively, it may also emerge from a pentagon or one of the many shapes that potentially contain it. But these are marginal results. Clearly, the golden ratio is not intended to govern a Gothic plan.

As Canon Charles J. Ledit wrote: "It will always be possible to establish relationships (golden or otherwise) between any two points on the monument. A billiard ball, moved by an indefinite energy, will always end up (thanks to the cushions) touching the other two balls. If you draw enough lines between points on a plane, you'll always get some indication (convincing or not)". The myth of the golden ratio being used to direct the layout of Gothic cathedrals clearly needs to be exposed.

N.B. In the appendix to the book, you'll find additional information on Gothic proportions and the Golden Ratio, including a refutation of Professor Murray's analysis of Amiens Cathedral.

Commentaires

La démonstration de Pierre Bellenguez sur la géométrie des cathédrales est absolument remarquable de simplicité et d'efficacité. Elle est très convaincante, et en plus, très élégante, ce qui est bon signe. L'architecte Viollet le Duc avait lui aussi proposé en son temps une hypothèse de géométrie sacrée en étudiant les coupes des cathédrales, mais ses résultats n'étaient pas très probants. Les points de ses figures tombaient un peu n'importe où et l'ensemble manquait de la clarté qui arrive toujours lorsqu'on a découvert le principe directeur d'un dessin. La démonstration de Pierre Bellenguez tient elle bien mieux la route. Elle est donc supérieure à celle de l'immense Viollet le Duc, ce n'est pas rien. Franchement bravo.

David Orbach (Architecte - Ingénieur structure - Enseignant à l’Université Populaire de Caen de Michel Onfray)

JE VOUS CONSEILLE SANS RÉSERVE la lecture du nouvel opus de Pierre Bellenguez, consacré au décryptage des tracés géométriques de la basilique de Vézelay. En seulement quelques dizaines de pages et d'illustrations, sans sombrer un seul instant dans les spéculations zozotériques et en s'appuyant notamment à très bon escient sur un schéma explicite du carnet de Villard de Honnecourt, l'auteur fournit au lecteur des clés immédiatement compréhensibles, limpides, de la compréhension géométrique de l'édifice.

Jean-Michel Mathonière - Directeur éditorial chez Éditions Dervy - Historien des compagnonnages

Au cathédraloscope, nous présentons les travaux de Pierre Bellenguez qui développe le concept de matrice première qui permettre aux bâtisseurs de dresser d'une manière cohérente les plans d'élévation d'une cathédrale. Il démontre dans son livre "les cathédrales retracées" la pertinence de son hypothèse.

Cathédraloscope

Dans son livre, Pierre Bellenguez, passionné d’architecture gothique, décrypte les constructions des bâtisseurs en se mettant dans la peau de ces derniers. A l’aide de différentes cathédrales gothiques françaises, il réfute des théories populaires sur ces édifices et démontre l’usage des figures géométriques dans ces bâtiments. Il s’intéresse également au symbolisme présent au cœur des cathédrales en analysant différents éléments architecturaux et historiques. Son œuvre nous a été particulièrement utile afin d’illustrer les méthodes géométriques des cathédrales gothiques [...]

Site : lescathedrales.wordpress.com

Un ouvrage extraordinaire où l’on ne fait pas de rapport entre la distance de la terre à la lune avec l’hypoténuse de la face de la pyramide en vraie grandeur, mais où les tracés sont opératifs […] car tout commence, quelle que soit l’épure […] en trait carré.

Jean-Pierre Bourcier - Spécialiste du trait

Pierre Bellenguez, déjà auteur d'un ouvrage sur les cathédrales, propose, avec ce livret, de découvrir l'univers de la basilique de Vézelay autrement, en essayant de comprendre comment celle-ci a été bâtie, quels symboles géométriques renferme-t-elle, en étudiant le portail et les symboles représentés. Un volume richement illustré (photos, plans, coupes, élévations) à lire d'urgence !

Olivier Petit - Médiéviste

Le Livre du Jour est : Les cathédrales retracées Les nombres régissent nos grands édifices. Pour bien le comprendre, il faut sortir ses outils de géomètre et chercher les proportions. Un travail méthodique et plein de bon sens dans les nefs, croisées et transepts, dans les absides et les chevets, et bien sûr dans les élévations. Une promenade qui nous conduit à Amiens, Vézelay, Beauvais, Chartres Bourges et Reims … Un bonheur d’ouvrage que nous devons à Pierre Bellenguez

Jean-François Lecompte - écrivain

Je recommande... Le superbe ouvrage Les cathédrales retracées pour tous les passionnés d'architecture gothique. Dans son livre, l'auteur Pierre Bellenguez nous dévoile le message caché derrière les plans des grandes cathédrales gothiques. À consommer sans modération !

Luciano Xavier - Maquettiste en cathédrales gothiques

Dans ce livre, je m'attendait à entendre beaucoup parler de géométrie sacrée, de traditions et de société secrète et bien pas du tout... Pour mon plus grand bonheur et mon plus grand plaisir, c'est un livre précis, sourcé, technique, néanmoins facile d'accès, qui permet à un néophyte d'aborder le sujet sans difficultés. L'auteur est très pédagogue, ça se lit tout seul. [...] Clairement, ce livre va véritablement m'aider pour mon travail sur les mystères des cathédrales. [...] Encore une fois je remercie chaleureusement Pierre Bellenguez pour son livre les cathédrales retracées.

Arcana Les Mystères du Monde - Youtubeur (Chaine Arcana)

Avis de lecteur (Priceminister) Beau et instructif. Ouvrage superbe avec d'abondantes illustrations en noir ou couleurs. Avec une simplicité communicative, l'auteur décrypte la science des bâtisseurs. Il réécrit avec clarté et à l'aide d'abondantes études personnelles les techniques qui ont permis cette révolution dans l'architecture. Loin d'être un remake de littératures courantes, c'est un beau livre à offrir ou à se faire offrir.

troph38

Le Mot du Jour est : « Encore Vézelay »? Un livret abondamment illustré sur la géométrie particulière de Vézelay vient d’être édité par Pierre Bellenguez. Ayant eu le privilège de le lire avant l’impression je vous le recommande, car compas en mains c’est de la belle ouvrage ! Les illustrations sont superbes et pédagogiques, alors, comme en plus c’est pas cher (15€), que ça s’achète en ligne et que ça tiendra dans le sac de plage, offrez-le-vous au plus vite !

Jean-François Lecompte - écrivain

J'ai lu votre livre d'une traite et vais bientôt le relire plus lentement. Merci et bravo, vous avez répondu à tellement de mes questions.

John Brown

Formidable ouvrage technique touffu mais très intéressant pour qui s’intéresse à cette magnifique architecture et à l’art des bâtisseurs... Merci Monsieur

Armand Priest (ESTP) - Commentaire Facebook

Pierre Bellenguez explique très bien le sens de la géométrie des cathédrales en prenant appui sur la basilique de Vézelay, dans son ouvrage [...] Les cathédrales retracées : la science des bâtisseurs

Anthony CRESTIN - La géométrie et le mythe

Passionné d'architecture, Pierre Bellenguez a repris les mesures des cathédrales et compris comment les bâtisseur ont réussi ces exploits architecturaux. Aucun nombre magique, mais du bon sens, de la simplicité et de l'expérience.

Joël Supéry - Site tuskaland.com

Regard d'un passionné d'architecture médiévale sur l'architecture secrète des cathédrales et la géométrie gothique. Un ouvrage très utile pour notre projet #STEAMBuilders (https://steambuilders.eu/fr/) qui a pour objectif de fournir aux enseignants des outils et la pédagogie nécessaires à la mise en œuvre de l'approche innovante et pluridisciplinaire des STEAM par la manipulation et la reconstruction de techniques et de patrimoine historiques !

Asso Fermat-Science

J'ai bien reçu votre admirable livre "Les cathédrales retracées" et je vous en remercie. Étant passionné par l'architecture sacrée j'ai pu l'apprécier. Encore merci. Cordialement,

M. Moldovan

"Dans le sillage du livre "Les cathédrales retracées", Pierre Bellenguez nous entraîne dans une visite initiatique de la basilique de Vézelay, à la découverte des procédés géométriques utilisés par les moines bâtisseurs. Compas en main, il nous fait découvrir l’alphabet de ce livre de pierre, la fascinante science des anciens maîtres d’œuvre". La basilique de Vézelay, un incontournable... !

Catherine Leschenne

Après son magnifique ouvrage intitulé : " Les cathédrales retracées ", je vous recommande vivement de découvrir le nouvel opus de l'excellent Bellenguez Pierre, consacré au décryptage des tracés géométriques de la basilique de Vézelay.

Dominique Gury