Gothic chevets

it was then that I saw the Pendulum. The sphere, moving at the end of a long wire attached to the choir vault, described its ample oscillations with isochronous majesty.

Umberto Eco(Foucault's Pendulum)

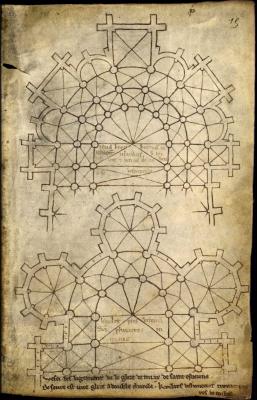

It's interesting to study the construction of the polygons that form the apses. On many monuments, you'll notice that the diagonal of the last bay of the choir directly prepares the angle of the polygon. By design, by the choice of an initial proportion, the final layout is anticipated. For those in doubt, note that Villard de Honnecourt drew these lines with the same pencil stroke (Fig. 1),

Fig. 1 - Chevet plans (Villard de Honnecourt - folio 29) D.P.

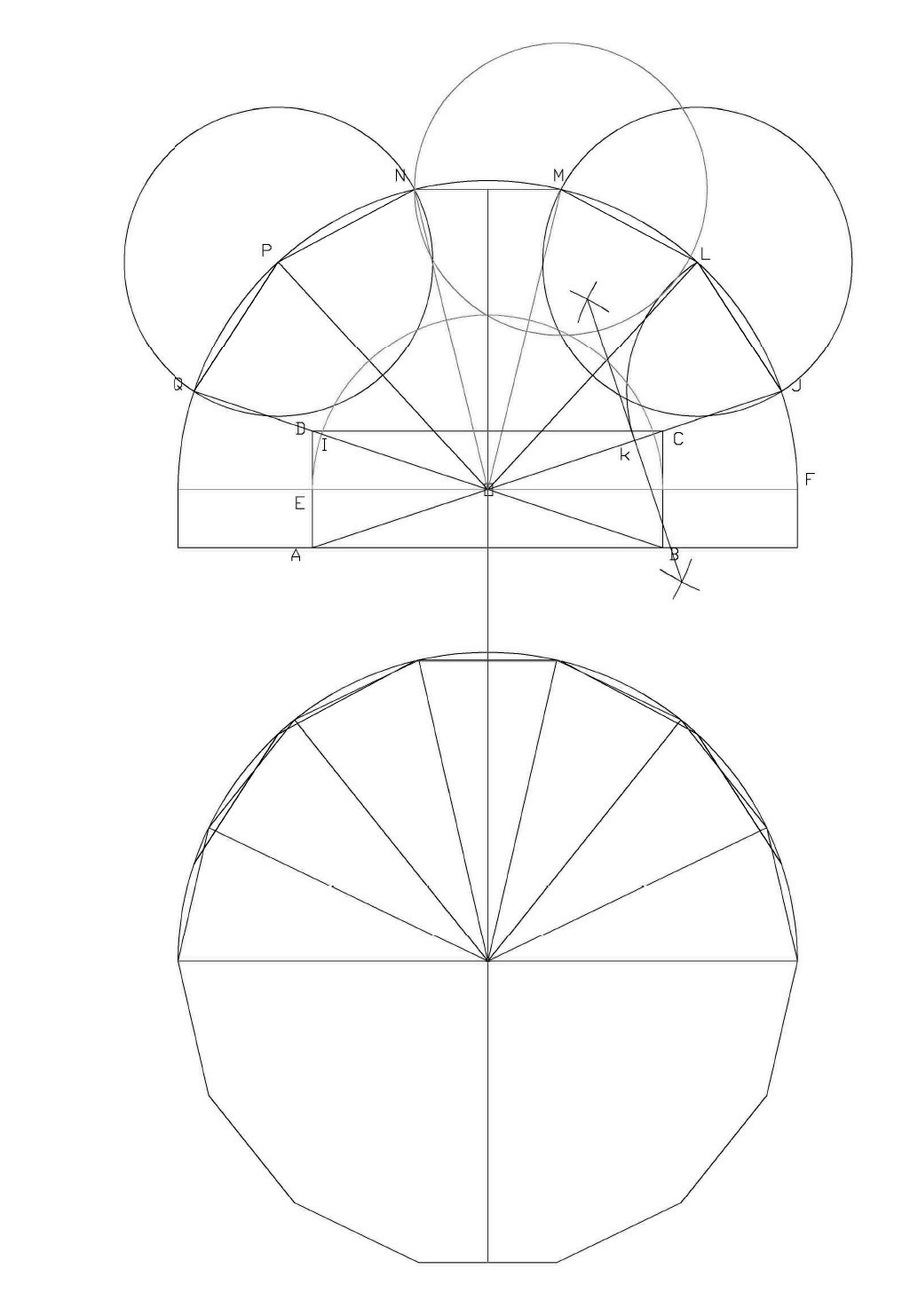

I've developed a number of procedures for drawing this type of cut. Here's a particularly interesting one (fig. 2). On the last bay of the choir, a square is defined, the diagonal of which is equal to half the width of the main nave (as shown by the dotted arc).

The height of this square is used to mark the apse's boundary. At the upper ends of the rectangle thus formed, I mark the pillars, and trace the semicircle of the apse with center O. From the lower corners, I draw two lines that intersect at O, defining two further pillars and cutting the circle.

The distance between the pillars we've just defined determines two of the sides we're looking for. All we need to do is transfer them symmetrically to complete the circle's partition.

Fig. 2 - Dividing an apse into five parts

The procedure we've just described is used to design the last bay of the choir and the chevet of many Gothic buildings. It can be found in Reims, the Abbey of Saint-Martin-aux-Bois and the Royal Collegiate Church of Saint-Quentin.

The chevets, crowned by seven chapels (fig. 3), are built in the same style. The width of the central nave is divided into three parts, creating a three-by-one rectangle inside the apse. The intersection of the diagonals (point O) will provide the origin of the circles, while their extensions will create the starting angle and fix the position of the columns.

Fig. 3 - Dividing an apse into seven parts

Knowing that half the length of the straight line is equal to the value to be transferred to the circle to form the angles, it's easy to draw the pseudo-heptagon. These are, in fact, one-by-two triangles, arranged in a fan-shape. The process is used in Beauvais and Amiens, among others.

Both are generic systems. Some cathedrals, such as Chartres, have their own specific layout.

I'll use the abbey church of Saint-Martin-aux-Bois in the Oise region to illustrate this point (fig. 4). The building features a transeptless aisle, enclosed by an apse similar to that of Reims.

Fig. 4 - Choir of Saint-Martin-aux-Bois

We've just seen that the side of the square determines the width of the last bay, while its diagonal is equivalent to the half-length of that same bay. To plot the height of the nave bays, the architect simply used this half-width to form equilateral triangles. There are two such triangles per bay. This segment (the red lines) is common to the entire building. It alone explains the eurhythmics.

In this example, it's hard to tell where the layout of the choir and nave begins. Here, they are part of the same nature. You can see a laser scan of this building at saint-martin-aux-bois.org

Traces of the apses of Mont Saint-Michel abbey and Notre-Dame d'Évreux

In the report "Mont-Saint-Michel - Le labyrinthe de l'archange" at 1h 15' 52'' , medieval art history professor Yves Gallet highlights a correspondence of proportions between the apse of this abbey and that of Évreux cathedral. He also notes that some of the choir's piers are lined with Romanesque supports, as are the crypt's columns. Understandably, the architect was forced to follow a pre-existing Romanesque rhythm.

The question then arises: since the chevet of Troyes cathedral is similar to that of Le Mont, isn't it itself a reflection of a Romanesque process? The history of Notre-Dame d'Évreux seems to invalidate this hypothesis. According to Philippe Gavet, the ancient Romanesque cathedral of Évreux is similar to the Abbatiale de la Trinité in Caen, whose chevet is segmented into five parts rather than seven. However, this element alone cannot dismiss the hypothesis.

In terms of geometric layout, the segmentation of the chevets at Évreux and Le Mont is the simplest imaginable. The width of the nave is divided into seven parts, seven units. The semicircle of the choir is set one unit apart. From one edge of the chancel, an arc with a radius of two units, an arc equal to half the width of the nave, and an arc equal to five units are drawn. By intersecting the semicircle, these arcs determine the exact centers of the piers.

as can be imagined, the segmentation obtained by this process is not regular, but the exact same deviations can be seen on the plans.

Mr. Jean Pierre Bourcier, a specialist in technical lines and stereotomy, checked my geometric demonstrations from a digital point of view. I'd like to share with you his analysis and opinion on the tracings we've just seen.

Analysis of the plot in figure 2 (created with AutoCAD)

"Let (A,B) be the width of the nave and (U,V) its axis. From point B, trace (B,M) such that the angle (A,B,M) is equal to 45°. Draw the arc of a circle with radius (B,U) and center B. It intersects (B,M) at I. From I, draw a line (D,C) parallel to (A,B). This line marks the boundary of the choir.

Let O be the midpoint of (D,C) and draw the line (O,B). It intersects the semicircle of radius (O ,D) at P, which is the center of the second stack, D being the position of the first stack. To trace the centers of the other stacks, simply transfer the chord (D,P) to (P ,Q) and then (Q,R). As you can see, the QT chord is larger than the DP chord.

If we keep the point P and its symmetrical W as a reference, and the point Q and its symmetrical T defined by transferring the chord (D,P), then the chord (Q,T ) is greater than the other four.

Let DP=CW=WT=PQ with QT > DP, which for a nave 12 m wide gives DP =3634.87 QT=4000, while the side of the decagon inscribed in the circle of radius OD is 3708.3

If we consider point T, the deviation between this plot and the plot of the theoretical decagon is 145.33 mm along an axis perpendicular to the nave axis and 49.48 mm along an axis parallel to the nave axis, with the center of the pile remaining on the circle of radius OD. In view of the function of the pile and the measuring instruments used at the time, the deviation is quite acceptable."

Figure 3 plot analysis:

"Let AB be the width of the nave and UV its axis AB is divided into three equal parts. The rectangle ABCD with short sides AB/3 is drawn. The two diagonals are drawn, and at their intersections the point O is the center of the circular axes of the piers. This point O is also the point of intersection of the radiating axes of the piles.

Let the circle of radius OE be the center of the first stack, its point of intersection I with the diagonal OD.

Let the center of the stacks located on the circle of radius OF be drawn. The diagonal OC is extended are intersection with the circle of radius OF defines the center of the first stack at J.

If K is the midpoint of OJ, the segment JK is the chord to be plotted on the circle of radius OF to obtain the points L and M, the centers of the next two piles JL= JK LM = OJ/2.

By symmetry with respect to the nave axis, we define the points N P and Q, centers of the following piers. The intersection of the straight lines radiating at O and passing through the centres of the piers of the circle of radius OF with the circle of radius OE defines the centers of the piers belonging to this circle.

We then see that JL=LM =NP =PQ with MN < JL, which gives for a nave 12 m wide and OF = 10616 (any value) JL=5308 MN=5012.34 the side of the 14-sided regular polygon inscribed in the circle of radius 0F being 4724.56

If we consider point M, the deviation between this layout and the layout of the 14-sided regular polygon inscribed on the circle of radius OF is 143.9 mm along an axis perpendicular to the nave axis and 33.9 mm along an axis parallel to the nave axis, with the center of the pile remaining on the circle of radius OF. In view of the function of the pile and the measuring instruments used at the time, this is perfectly acceptable."

Commentaires

La démonstration de Pierre Bellenguez sur la géométrie des cathédrales est absolument remarquable de simplicité et d'efficacité. Elle est très convaincante, et en plus, très élégante, ce qui est bon signe. L'architecte Viollet le Duc avait lui aussi proposé en son temps une hypothèse de géométrie sacrée en étudiant les coupes des cathédrales, mais ses résultats n'étaient pas très probants. Les points de ses figures tombaient un peu n'importe où et l'ensemble manquait de la clarté qui arrive toujours lorsqu'on a découvert le principe directeur d'un dessin. La démonstration de Pierre Bellenguez tient elle bien mieux la route. Elle est donc supérieure à celle de l'immense Viollet le Duc, ce n'est pas rien. Franchement bravo.

David Orbach (Architecte - Ingénieur structure - Enseignant à l’Université Populaire de Caen de Michel Onfray)

JE VOUS CONSEILLE SANS RÉSERVE la lecture du nouvel opus de Pierre Bellenguez, consacré au décryptage des tracés géométriques de la basilique de Vézelay. En seulement quelques dizaines de pages et d'illustrations, sans sombrer un seul instant dans les spéculations zozotériques et en s'appuyant notamment à très bon escient sur un schéma explicite du carnet de Villard de Honnecourt, l'auteur fournit au lecteur des clés immédiatement compréhensibles, limpides, de la compréhension géométrique de l'édifice.

Jean-Michel Mathonière - Directeur éditorial chez Éditions Dervy - Historien des compagnonnages

Au cathédraloscope, nous présentons les travaux de Pierre Bellenguez qui développe le concept de matrice première qui permettre aux bâtisseurs de dresser d'une manière cohérente les plans d'élévation d'une cathédrale. Il démontre dans son livre "les cathédrales retracées" la pertinence de son hypothèse.

Cathédraloscope

Dans son livre, Pierre Bellenguez, passionné d’architecture gothique, décrypte les constructions des bâtisseurs en se mettant dans la peau de ces derniers. A l’aide de différentes cathédrales gothiques françaises, il réfute des théories populaires sur ces édifices et démontre l’usage des figures géométriques dans ces bâtiments. Il s’intéresse également au symbolisme présent au cœur des cathédrales en analysant différents éléments architecturaux et historiques. Son œuvre nous a été particulièrement utile afin d’illustrer les méthodes géométriques des cathédrales gothiques [...]

Site : lescathedrales.wordpress.com

Un ouvrage extraordinaire où l’on ne fait pas de rapport entre la distance de la terre à la lune avec l’hypoténuse de la face de la pyramide en vraie grandeur, mais où les tracés sont opératifs […] car tout commence, quelle que soit l’épure […] en trait carré.

Jean-Pierre Bourcier - Spécialiste du trait

Pierre Bellenguez, déjà auteur d'un ouvrage sur les cathédrales, propose, avec ce livret, de découvrir l'univers de la basilique de Vézelay autrement, en essayant de comprendre comment celle-ci a été bâtie, quels symboles géométriques renferme-t-elle, en étudiant le portail et les symboles représentés. Un volume richement illustré (photos, plans, coupes, élévations) à lire d'urgence !

Olivier Petit - Médiéviste

Le Livre du Jour est : Les cathédrales retracées Les nombres régissent nos grands édifices. Pour bien le comprendre, il faut sortir ses outils de géomètre et chercher les proportions. Un travail méthodique et plein de bon sens dans les nefs, croisées et transepts, dans les absides et les chevets, et bien sûr dans les élévations. Une promenade qui nous conduit à Amiens, Vézelay, Beauvais, Chartres Bourges et Reims … Un bonheur d’ouvrage que nous devons à Pierre Bellenguez

Jean-François Lecompte - écrivain

Je recommande... Le superbe ouvrage Les cathédrales retracées pour tous les passionnés d'architecture gothique. Dans son livre, l'auteur Pierre Bellenguez nous dévoile le message caché derrière les plans des grandes cathédrales gothiques. À consommer sans modération !

Luciano Xavier - Maquettiste en cathédrales gothiques

Dans ce livre, je m'attendait à entendre beaucoup parler de géométrie sacrée, de traditions et de société secrète et bien pas du tout... Pour mon plus grand bonheur et mon plus grand plaisir, c'est un livre précis, sourcé, technique, néanmoins facile d'accès, qui permet à un néophyte d'aborder le sujet sans difficultés. L'auteur est très pédagogue, ça se lit tout seul. [...] Clairement, ce livre va véritablement m'aider pour mon travail sur les mystères des cathédrales. [...] Encore une fois je remercie chaleureusement Pierre Bellenguez pour son livre les cathédrales retracées.

Arcana Les Mystères du Monde - Youtubeur (Chaine Arcana)

Avis de lecteur (Priceminister) Beau et instructif. Ouvrage superbe avec d'abondantes illustrations en noir ou couleurs. Avec une simplicité communicative, l'auteur décrypte la science des bâtisseurs. Il réécrit avec clarté et à l'aide d'abondantes études personnelles les techniques qui ont permis cette révolution dans l'architecture. Loin d'être un remake de littératures courantes, c'est un beau livre à offrir ou à se faire offrir.

troph38

Le Mot du Jour est : « Encore Vézelay »? Un livret abondamment illustré sur la géométrie particulière de Vézelay vient d’être édité par Pierre Bellenguez. Ayant eu le privilège de le lire avant l’impression je vous le recommande, car compas en mains c’est de la belle ouvrage ! Les illustrations sont superbes et pédagogiques, alors, comme en plus c’est pas cher (15€), que ça s’achète en ligne et que ça tiendra dans le sac de plage, offrez-le-vous au plus vite !

Jean-François Lecompte - écrivain

J'ai lu votre livre d'une traite et vais bientôt le relire plus lentement. Merci et bravo, vous avez répondu à tellement de mes questions.

John Brown

Formidable ouvrage technique touffu mais très intéressant pour qui s’intéresse à cette magnifique architecture et à l’art des bâtisseurs... Merci Monsieur

Armand Priest (ESTP) - Commentaire Facebook

Pierre Bellenguez explique très bien le sens de la géométrie des cathédrales en prenant appui sur la basilique de Vézelay, dans son ouvrage [...] Les cathédrales retracées : la science des bâtisseurs

Anthony CRESTIN - La géométrie et le mythe

Passionné d'architecture, Pierre Bellenguez a repris les mesures des cathédrales et compris comment les bâtisseur ont réussi ces exploits architecturaux. Aucun nombre magique, mais du bon sens, de la simplicité et de l'expérience.

Joël Supéry - Site tuskaland.com

Regard d'un passionné d'architecture médiévale sur l'architecture secrète des cathédrales et la géométrie gothique. Un ouvrage très utile pour notre projet #STEAMBuilders (https://steambuilders.eu/fr/) qui a pour objectif de fournir aux enseignants des outils et la pédagogie nécessaires à la mise en œuvre de l'approche innovante et pluridisciplinaire des STEAM par la manipulation et la reconstruction de techniques et de patrimoine historiques !

Asso Fermat-Science

J'ai bien reçu votre admirable livre "Les cathédrales retracées" et je vous en remercie. Étant passionné par l'architecture sacrée j'ai pu l'apprécier. Encore merci. Cordialement,

M. Moldovan

"Dans le sillage du livre "Les cathédrales retracées", Pierre Bellenguez nous entraîne dans une visite initiatique de la basilique de Vézelay, à la découverte des procédés géométriques utilisés par les moines bâtisseurs. Compas en main, il nous fait découvrir l’alphabet de ce livre de pierre, la fascinante science des anciens maîtres d’œuvre". La basilique de Vézelay, un incontournable... !

Catherine Leschenne

Après son magnifique ouvrage intitulé : " Les cathédrales retracées ", je vous recommande vivement de découvrir le nouvel opus de l'excellent Bellenguez Pierre, consacré au décryptage des tracés géométriques de la basilique de Vézelay.

Dominique Gury